Learn how HealthPartners builds an ethical culture that promotes compliance.

“Should we follow the rules, or should we do the right thing?” It’s a question that’s familiar to most compliance professionals. So often organizations find themselves caught between what regulations say they should do and what their organizational values would have them do. But just as tricky is when there really isn’t a set of rules “or even a set of values” to give us a road map for navigating tough situations. What then?

At HealthPartners, a Minnesota-based integrated health care delivery and financing organization, we recently encountered an emerging issue that is a good example of this kind of dilemma: what do we do when neither the law nor our values give us a clear path for addressing a critical problem?

In the fall of 2016, HealthPartners launched a series of conversations about race as part of a twice-yearly activity we call Team Talks. Team Talks give colleagues at over 250 locations across the organization a chance to talk with senior leaders about topics that matter most to them, and to our patients, members and community. We began the fall 2016 Team Talks by acknowledging that race can be difficult to talk about for some people, especially in a work setting, while it is more comfortable for others. “Wherever you are,” we said, “we hope everyone can contribute something today. None of us are experts, but we all have our own experiences. So let’s create a space today where we can all learn from different perspectives and experiences.” As a leader-facilitator of several of these conversations, I was privileged to hear colleagues “many of whom I have worked with for over two decades” tell personal stories that gave me a new appreciation for who they are. It was an invaluable and humbling experience.

One surprising – and uncomfortable – issue that frequently came up during those Team Talks was that employees in a variety of roles and locations reported interacting with patients and members who had refused care or service from them, apparently in response to the employee’s race, language, ethnicity, LGBTQ status, gender, country of origin or religion. Other colleagues reported different forms of bias from patients and members, such as harshly questioning the credentials of a caregiver who appeared to be foreign born or interrogating a lab technician who was wearing a head scarf about her views on terrorism. And these expressions of patient and member bias were happening with increasing frequency.

This was concerning and presented a complex and difficult dilemma. Every patient and member carries their own personal experiences, and there may, in some cases, be understandable reasons why a person is not comfortable with a particular caregiver. Moreover, people are not always at their best when they are in extreme pain, are experiencing a health crisis or feel frightened in an unfamiliar environment. At the same time, as our Diversity and Inclusion philosophy states, we want to create an environment where every person – every patient, member, family member and colleague – feels welcomed, valued and included. Our colleagues wanted to know: should we accommodate patient and member requests – in some cases, demands – to work only with employees whose outward appearances, accents and faiths aligned with their own? Or should we refuse such demands, instead telling the people we are here to serve that . . . well, we would not be serving them? What was the right thing to do?

We knew we had to address this issue. Not only did these requests and behaviors undermine our values and efforts to be inclusive, they were also hurtful to our skilled and caring colleagues. We knew, too, that if not handled appropriately, these interactions could create legal risk for the organization and ultimately undermine the quality and safety of care and service we strive to give to our patients and members. But there are few laws that address patient and member demands and behavior of this nature – and merely complying with those laws would do little to mitigate our risk. Turning to our organizational values of Excellence, Partnership, Compassion and Integrity was not immediately helpful, either. Depending on whom you asked, those values could either lead us to accommodating all patient demands and behaviors, no matter how outrageous or hurtful, or to protecting the dignity and diversity of our workforce, no matter what the patient or member was asking for. There would be no easy answers to this issue, but for the sake of our colleagues – and our patients and members – we did need some answers.

We began to look for those answers by doing what we do quite well at HealthPartners: We talked. We convened a team of leaders from Diversity & Inclusion, Patient Care, Member Experience, Integrity & Compliance, Human Resources, Bioethics, and Communications. Amid much impassioned conversation, the group quickly agreed that, while we needed standards for how to address patient and member bias, no single policy could address the myriad manifestations of this issue.

So we did another thing we tend to do a lot at HealthPartners: We wrote. We started by articulating several rights, responsibilities and values, that come into play – and sometimes come into conflict – when we are faced with instances of patient and member bias, including: our organizational Vision (“Health as it could be, affordability as it must be, through relationships built on trust”); patient autonomy; professionals obligations to do no harm to the people we serve; colleagues right to work in a safe, harassment-free environment; and a variety of legal obligations. From there, we drafted a series of Principles that we hoped would help guide colleagues through these situations.

And then: We listened. We took the draft Principles to a number of stakeholder groups; most significantly, we met with a number of colleagues who had directly experienced patient or member bias in some form. We heard incredible stories of empathy, grace and even humor in the face of some very difficult situations. These conversations made it clear that people needed clearer decision paths, more concrete steps to follow, and more specific, appropriate language to use. They needed to know whether they would be supported by their employer, their leaders, and their coworkers. And they needed to know how to make difficult care and service choices in the moment.

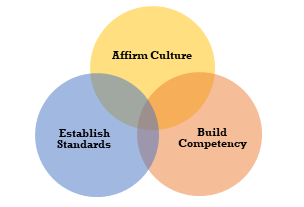

In other words, in addition to affirming our diverse and inclusive culture, we needed to be more specific about our standards and to build competency. (See Fig. A.) So we wrote some more. This time, we brought the Principles into the real world (see Fig. B), and created a toolkit for employees, based in large part on the conversations we had with so many of our compassionate, wise colleagues. The toolkit includes a step-by-step guide to help colleagues plan and practice for these situations, to help de-escalate, communicate and support each other during difficult interactions, and to facilitate reporting, follow-up and team culture after the situation has been addressed. It also includes scripting for all colleagues – from the person who is the direct target of patient or member bias, to the person who receives a complaint about another colleague, to the leader who is called upon to facilitate a resolution. The toolkit also features a video of colleagues describing their experiences, an e-learning module, and template communications.

This spring, to launch the toolkit – to affirm our culture, communicate our standards and build colleagues competency – we went back to where we started eighteen months ago: with Team Talks. Our Spring 2018 Team Talks were designed around about patient and member bias: how it shows up; what we, through our own biases, assume (rightly and wrongly) about it; the importance of supporting colleagues; and how to address it in a way that both honors our organizational values and complies with the law.

Yes, we’re back to that: when neither organizational values nor the law gives us clear answers, or a clear path to answers, what do we do?

In an organization with a culture of compliance and ethics, we did this: We engaged with stakeholders and heard things that surprised us and sometimes made us uncomfortable. We brought multiple perspectives to the conversation and humbly acknowledged that what we had to offer wasn’t enough. We then talked more with stakeholders and learned even more from them. We affirmed our culture, established standards, and built competency, so that every colleague touched by this difficult issue felt the decisions they made were aligned with our values and our responsibilities. That’s our sweet spot.

Fig. B

HealthPartners Principles for Addressing Patient and Member Bias

1. Clinical Stability of the Patient Is Primary.

This should always be the primary and foremost factor in decision-making; all of the remaining principles should be considered once the individual is clinically stable.

2. Communication Is Critical

Stresses the importance of communicating openly with a patient or member to understand and respond to their concerns, express support for and confidence in the skills of our colleagues and keep the focus on patient care and member service, with leader intervention as needed.

3. Capacity of the Patient or Member Must Be Evaluated

Recognizes that in some situations, patients and members may not be responsible for their behavior, due, for example, to mental illnesses or conditions and impaired judgment; our ability to respond to individual requests or tolerate certain behaviors will increase as needed to provide safe care for people who have less capacity to control or understand their behavior.

4. Cultural and Personal Context Are Relevant

Reflects the fact that some requests to change caregivers may be due to an individual’s cultural background or personal history, as opposed to bias, disrespect or blatant discrimination; at the same time, cultural/personal context is never justification for disrespectful or abusive behavior toward a colleague, which will not be tolerated; in all interactions, we strive to lead with cultural humility, avoiding assumptions and seeking to understand patient and member needs.

5. Caregivers and Other Colleagues Must Be Supported

Empowers colleagues and encourages them to report inappropriate words and behaviors when observed, even if not directed at them personally; the burden of recognizing and responding to intolerance and discrimination should not be borne solely by the person being targeted; when possible, caregivers and other colleagues should be consulted before any decisions are made regarding a change request; colleagues may choose to continue caring for the individual if they believe they can do so safely, objectively and professionally.

6. Personal Safety Is Important

Stresses that some situations are so sensitive that, if we insist a person is cared for or served by a particular colleague, the patient, member, or colleague, might suffer physical or psychological harm.

7. Legal Requirements Must Be Followed

Recognizes the importance of being aware of and complying with applicable laws and professional standards.

© HealthPartners, Inc. 2017

By: Tobi Tanzer, vice president, Integrity and Compliance and Chief Compliance and Privacy Officer at Health Partners.

This article originally appeared in the Center for Ethics in Practice newsletter in Winter 2018.